Scientists in the US have devised a new way to grow skin in 3D shapes, including an artificial ‘glove’ that could be worn on a severely burned hand.

The study, from bioengineers at Columbia University, also found that the 3D grafts work better than conventional pieced-together grafts.

The findings are published in Science Advances.

Lead developer Hasan Erbil Abaci, PhD, assistant professor of dermatology at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons, said:

“Three-dimensional skin constructs that can be transplanted as ‘biological clothing’ would have many advantages.

“They would dramatically minimise the need for suturing, reduce the length of surgeries, and improve aesthetic outcomes.”

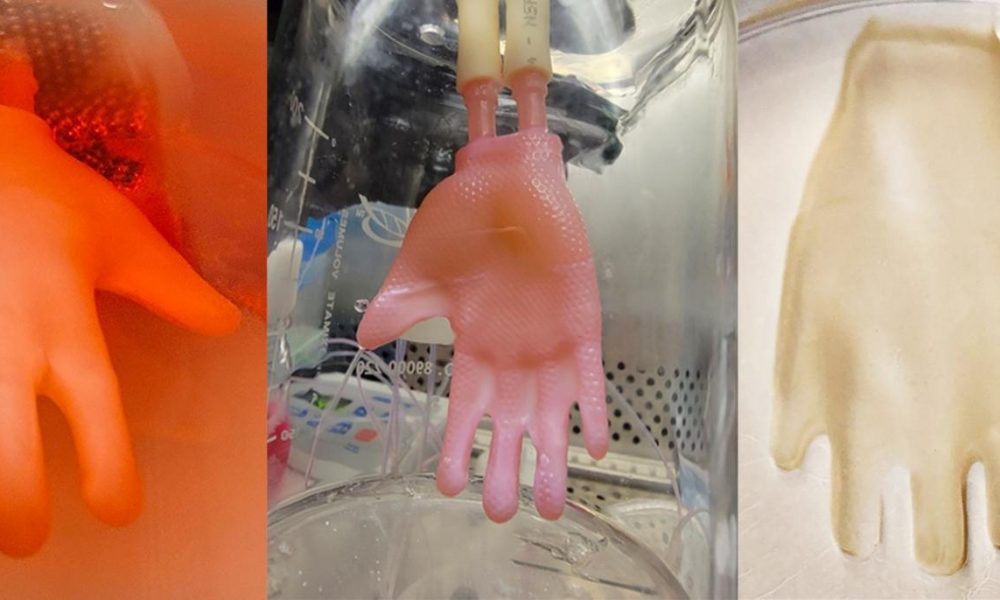

The process of creating the new skin grafts starts with a 3D laser scan of the target structure, such as a human hand.

Then, a hollow, permeable model of the hand is crafted using computer-aided design and 3D printing.

The exterior of the model is then seeded with skin fibroblasts – cells that help form connective tissue, and collagen, a structural protein.

Finally, the outside of the mould is coated with a mixture of keratinocytes (cells that comprise most of the outer skin layer, or epidermis) and the inside is perfused with growth media, which help to nourish the developing graft.

The 3D grafts represent the first major re-design of engineered skin grafts since they were first introduced in the early 1980s.

Abaci said:

“Engineered skin started with only two cell types, but human skin has around 50 types of cells.

“Most research had focused on mimicking the cellular components of human skin.

“As a bioengineer, it’s always bothered me that the skin’s geometry was overlooked and grafts have been made with open boundaries, or edges.

“We know from bioengineering other organs that geometry is an important factor that affects function.”

The researcher envisions that the grafts could one day be custom-made from a patient’s own cells.

A 4X4 mm skin sample would provide enough cells to be cultured and multiplied to create a skin that covers the human hand.

Abaci said:

“Another compelling use would be face transplants, where our wearable skin would be integrated with underlying tissues like cartilage, muscle, and bone, offering patients a personalised alternative to cadaver transplants.”

Image: Columbia University